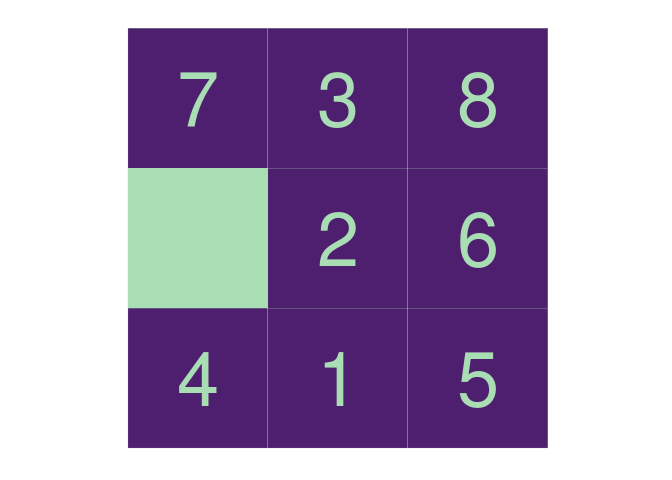

The 8-puzzle

The 8-puzzle is a game featuring a set of 8 numbered tiles on a 3x3 grid (leaving one blank cell). The objective is to get the tiles in numerical order by sliding them. The puzzlr package provides basic functions for creating and manipulating game boards.

library(puzzlr)

set.seed(9803808)

p <- random_puzzle(size = 3)

plot(p)

So, for instance, on this board I can move the 2 to the left, the 7

down, or the 4 up. The function neighbors() generates all possible

moves from a given game state:

neighbors(p)

## [[1]]

## . 3 . 8

## 7 . 2 . 6

## 4 . 1 . 5

##

## [[2]]

## 7 . 3 . 8

## 4 . 2 . 6

## . 1 . 5

##

## [[3]]

## 7 . 3 . 8

## 2 . . 6

## 4 . 1 . 5

Each move produces a new board that also holds a pointer to the previous board, so that we can always replay the moves we used to get to a particular state:

# the move() function requires the coordinates of the source and

# destination tile here i move the 7 down into the blank spot

moved_once <- move(p, source = c(1, 1), dest = c(2, 1))

replay_moves(moved_once)

## [[1]]

## 7 . 3 . 8

## . 2 . 6

## 4 . 1 . 5

##

## [[2]]

## . 3 . 8

## 7 . 2 . 6

## 4 . 1 . 5

Solving the puzzle

I’d like to find the solution that requires the fewest moves. The way I propose to do that is to generate a list of every playable game (here I define a “playable game” to be any possible sequence of moves), and then search through that list for those that end in the solution state. Finally, I take the one that has the fewest moves.

Alas, there are a frightful number of such games. From each puzzle state, there are 2 - 4 possible moves, so there are between 2n and 4n games of length n. Clearly I can’t expect to generate all possible games more than a dozen or so moves out. Instead of materializing all of them, I use the lazylist package to create a lazily evaluated list, or “stream,” of playable games of every length. If I construct the stream in such a way that the most promising games appear first, I can pick through the stream in order until I happen across a solution. Since the stream is lazily evaluated, I only have to expend the resources to generate the games that I actually investigate, rather than every possible one. If my ability to evaluate how “promising” a sequence is is any good, then I can constrain my efforts to a small fraction of the full solution space.

To construct a stream of all possible games playable from a given puzzle

state, I generate all games of 1 move, and then recursively generate all

possible games off of each of those. Finally, I braid together the

resulting streams of games, ordering them by a weight_function:

library(lazylist)

all_games_from <- function(pz, weight_function) {

possible_next_moves <- puzzlr::neighbors(pz)

possible_moves <- purrr::map(

possible_next_moves,

function(x)

cons_stream(x, all_games_from(x, weight_function) )

)

purrr::reduce(possible_moves,

merge_weighted,

weight = weight_function)

}

This is all a bit mind-bending if you’re not used to this style of

programming. This ability to define data structures recursively allows

us to model our problem in a more abstract way – we create objects

representing not a single move, but rather every possible sequence of

moves, and then manipulate these higher-level objects. The

merge_weighted function appears to be doing a lot of heavy lifting

here, but a look at the source

code

shows that it, too, has a surprisingly simple implementation. This is

all possible due to the magic of lazy evaluation.

The weight_function is the key to how efficiently our algorithm will

find a solution. The neighbors() function avoids any move that would

put the puzzle back into the same state it was one move previously, but

still the number of possible states that the game can reach grows

quickly as the number of moves increases:

So the fewer alternative routes we can visit at each stage, the more

quickly we’ll find the shortest solution to the puzzle. An algorithm for

solving just such a problem is the A*

algorithm, which

guarantees we’ll find the shortest solution to the puzzle (given one

exists), as long as our weight_function has this form:

moves(x) + ???(x)

moves() tells us how many moves were required to get the puzzle to

it’s current state. ???() is an estimate of the number of moves

remaining to the solution, and is called a heuristic. We can guarantee

that we’ll find the shortest possible solution if we know that ???()

never overestimates the number of moves remaining. However, the closer

it comes to correctly estimating, the more possible game paths we’ll be

able to ignore, thus reducing the time required to identify the game

path corresponding to the solution. We want ???() to get as close as

possible to the true number of moves remaining without going over.

The puzzlr package provides two built-in heuristics, hamming() and

manhattan(). We’ll use the manhattan distance:

mh_cost <- function(x) moves(x) + manhattan(x)

all_games <- all_games_from(p, weight_function = mh_cost)

Now that we have a stream representing every possible sequence of moves for our puzzle, we just pick out the ones that result in solutions. We know we’re at a solution if the manhattan distance is equal to 0, so:

is_solution <- function(x) manhattan(x) == 0

solutions <- stream_filter(all_games, is_solution)

To view the shortest solution:

animate_moves(solutions[1])

Analyzing performance

One advantage to working with streams is that we now have access to the entire history of the search process.

all_games includes every possible playable game, though I didn’t have

to evaluate every element, so I didn’t have to investigate every

possible game. I did, however, have to investigate every game in

all_games up to the first solution. I can review how many games I had

to investigate:

solution_index <- stream_which(all_games, is_solution)

solution_index[1]

## [1] 2680

The eventual solution was 25 moves, and based on the earlier discussion I know that there are between 33,554,432 and 1,125,899,906,842,624 possible games of length 25, so I guess 2,680 doesn’t seem so bad. Let’s look in more detail at what happened:

library(tidyverse)

investigated <- as.list(all_games, from = 1, to = solution_index[1])

investigated_df <- imap_dfr(

investigated,

~data_frame(timestamp = .y,

moves = moves(.x),

manhattan = manhattan(.x),

hamming = hamming(.x)))

investigated_df

## # A tibble: 2,680 x 4

## timestamp moves manhattan hamming

## <int> <int> <int> <int>

## 1 1 1 12 7

## 2 2 1 12 6

## 3 3 2 11 6

## 4 4 3 10 6

## 5 5 2 13 7

## 6 6 3 12 6

## 7 7 4 11 6

## 8 8 5 10 6

## 9 9 3 12 7

## 10 10 3 12 6

## # ... with 2,670 more rows

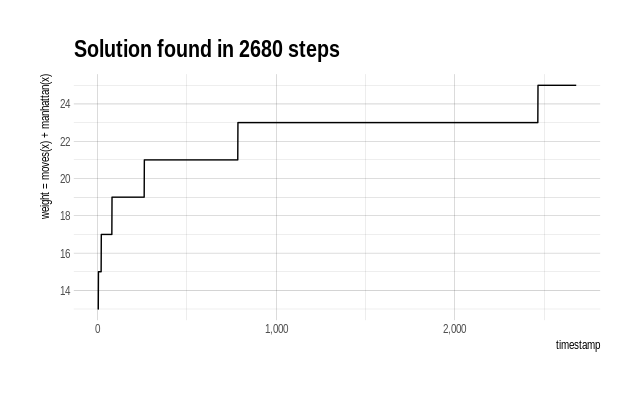

Let’s look at the values taken by the weight_function during the

search:

investigated_df %>%

mutate(weight = moves + manhattan) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = timestamp, y = weight)) +

geom_line() +

hrbrthemes::theme_ipsum() +

scale_x_continuous(labels = scales::comma) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = seq(from = 12, to = 26, by = 2),

name = "weight = moves(x) + manhattan(x)") +

ggtitle(paste("Solution found in", solution_index[1], "steps"))

I spent a lot of time looking at puzzle states that had weight 23. If there were some way of differentiating among these, maybe I could save some time. I see a similar story when looking at the number of moves of each investigated game state.

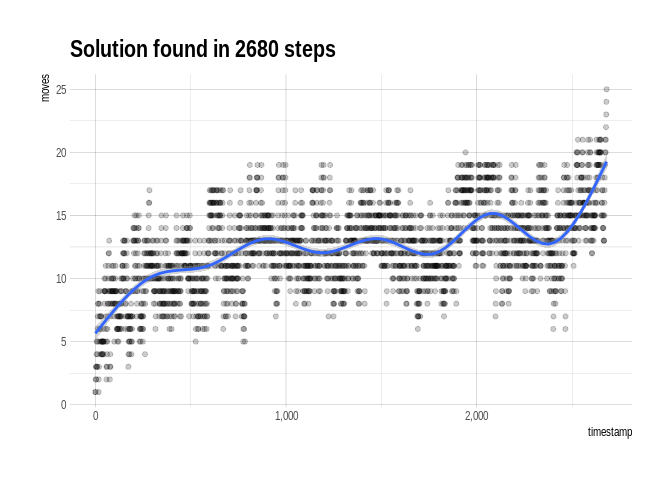

investigated_df %>%

ggplot(aes(x = timestamp, y = moves)) +

geom_point(alpha = .2) +

geom_smooth() +

hrbrthemes::theme_ipsum() +

scale_x_continuous(labels = scales::comma) +

ggtitle(paste("Solution found in", solution_index[1], "steps"))

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'gam' and formula 'y ~ s(x, bs = "cs")'

We spent a majority of the time investigating various games with lengths between 10 and 15, but once we discovered the correct path, we made our way to the full 25-move solution without much more dawdling.

At each step of a game, we choose between a number of available moves. So the overall search can be viewed as a directed graph, where we are searching for the correct path down the graph. Visualizing our search in terms of this graph tells a similar story, where we explored a large number of mid-length games before identifying the one that would lead to the solution, but once we found it we were able to move down it quickly without exploring its neighbors:

library(tidygraph)

library(ggraph)

# use digest::digest to create a unique identifier for each game

game_graph <- map_dfr(

investigated,

~data_frame(from = digest::digest(puzzlr::parent(.)),

to = digest::digest(.),

moves = moves(.)))

# identify the correct path in the graph so that we can highlight it

solution_step_ids <- map_chr(replay_moves(solutions[1]),

digest::digest)

game_graph <- game_graph %>%

mutate(is_solution = to %in% solution_step_ids)

as_tbl_graph(game_graph) %>%

ggraph(layout = "igraph", algorithm = "tree") +

geom_edge_diagonal0(aes(colour = is_solution,

width = is_solution)) +

scale_edge_colour_manual(values = c("TRUE" = "red",

"FALSE" = "gray60"),

guide = "none") +

scale_edge_width_manual(values = c("TRUE" = .3,

"FALSE" = .1),

guide = "none") +

theme_void()